(The Conversation) — At the outset of the Kalevala, Finland’s national epic, a singer bemoans his separation from a beloved friend who grew up beside him. Today, the friends rarely meet “näillä raukoilla rajoilla, poloisilla Pohjan mailla” – lines which translator Keith Bosley renders “on these poor borders, the luckless lands of the North.”

The Kalevala, a poetic masterpiece of nearly 23,000 lines, first appeared in 1835. Now, nearly 200 years later, those “luckless lands of the North” are an increasingly tense border zone.

On one side sits Finland, affluent and famously “happy.” The Nordic nation of 5.6 million is a member of the European Union and, more recently, the NATO alliance. On the other side sits the Republic of Karelia, with a population of around a half-million. Originally home to the Karelians, a people closely related to the Finns, today Karelia is part of the Russian Federation – and the percentage of Karelian speakers is in the single digits.

Finland celebrates Feb. 28 as Kalevala Day, or the “Day of Finnish Culture.” Yet the epic’s songs were collected in both Finland and Karelia, reflecting a cultural affinity sundered by the politics of empire. And as Russia’s war in Ukraine drags on, that border zone has become more tense.

Shared roots

The people of Finland and Karelia – “Suomi” and “Karjala,” in their own languages – have lived in the forests, lakes, marshes and farmlands of northeastern Europe since time immemorial. Their languages are closely related, but they differ markedly from Swedish and Russian, the idioms of the empires that usurped control over the region in the Middle Ages. Finns came under the dominion of Sweden and were converted to Roman Catholicism – and later Lutheranism. Karelians came under the dominion of Russia and were converted to Orthodox Christianity.

Centuries of wars and saber-rattling between the Swedish and Russian empires created hardship for Finns and Karelians alike. Their lands became battlegrounds for warring forces, and their men served as conscripted soldiers for opposing sides in conflicts like the Great Northern War of 1700–1721, which devastated both lands and populations.

Despite the enmity of rival emperors, over the course of centuries daily life and culture had remained remarkably similar for Finns and Karelians. Both sang songs of a mythic past, colorful heroes and powerful magic using a distinctive poetic meter – one that Henry Wadsworth Longfellow later imitated in “The Song of Hiawatha.”

Karelian singer Anni Kiriloff, born in 1886, sings about the mythical creation of the kantele, a five-stringed harp.

Mythic songs

In 1809, after yet another war, Russia acquired Finland as an autonomous grand duchy, bringing its people under the same crown as Karelians.

Finnish physician and admirer of folklore Elias Lönnrot took advantage of this political union to collect folk songs across the region. Wandering from village to village, writing down songs from dictation, he amassed a body of texts out of which to make an epic.

‘The Defense of the Sampo,’ by Finnish artist Akseli Gallen-Kallela.

Turku Art Museum via Wikimedia Commons

The contents of the Kalevala are varied and intriguing – starting with the creation of the Earth from an egg, and the felling of a primordial oak tree that threatened to block out the sun.

One of the epic’s most famous tales is the forging of a mysterious object, the Sampo – a sort of magic mill that will produce whatever its owner wishes. It becomes an object of conflict between the people of “Kalevala” and the people of “Pohjola,” the “north.”

The Kalevala hero Väinämöinen, a wizened worker of magic – along with Ilmarinen, the skilled but brooding blacksmith who originally created the Sampo, and their incorrigible friend, Lemminkäinen – attempt to steal the Sampo away from Pohjola, where Louhi, the stern Mistress of the North, has sequestered it. The resulting struggle destroys the Sampo, and its promised life of ease and prosperity.

‘Lemminkäinen’s Mother,’ by Finnish painter Akseli Gallen-Kallela, depicts her bringing one of the Kalevala’s heroes back to life.

Ateneum via Wikimedia Commons

Lönnrot hoped to unearth a history and an identity for Finns and Karelians, one separate from that of either Sweden or Russia. On the Finnish side of the border, in particular, the epic helped convince people that they were a valuable and creative nation, distinct from the empires that sought to control them.

As the 19th century wore on, the Russian government became less friendly to its cultural minorities. Authorities attempted to “Russify” Finland and other parts of the empire. But Finns resisted, drawing on images from Lönnrot’s Kalevala to articulate their cultural and historical independence.

The paintings of Akseli Gallen-Kallela drew on the epic for themes and inspiration at the turn of the 20th century. Composer Jean Sibelius’ famed Lemminkäinen Suite of 1896, or “Four Legends from the Kalevala,” made elements of the story familiar to audiences around the world and helped bolster international awareness of Finland’s culture. An early Finnish photographer, I.K. Inha, retraced Lönnrot’s wanderings through Finland and Karelia in a book entitled “Finland in Pictures.”

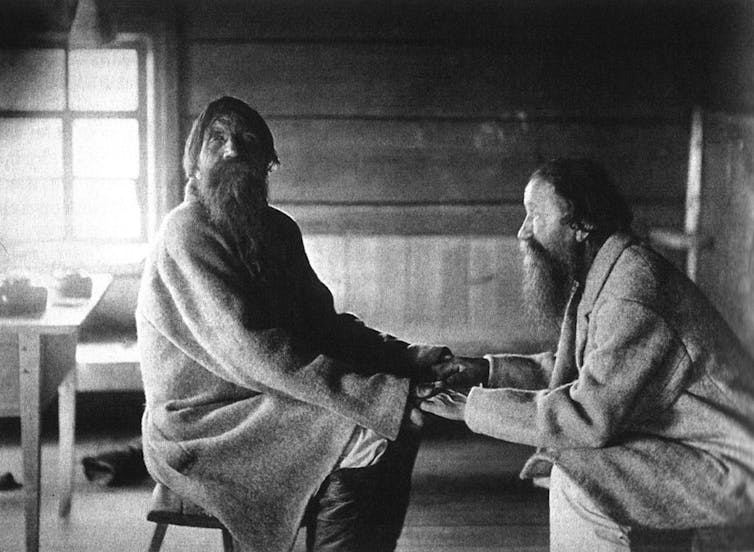

Brothers Poavila and Triihvo Jamanen recite traditional folk poetry in a Karelian village in 1894.

I. K. Inha/Wikimedia Commons

Independent Finland

Finland achieved independence in 1917, in the aftermath of Russia’s Bolshevik Revolution. But civil war soon broke out between the “Finnish Whites” and socialist “Finnish Reds.” It was the first of several conflicts that shifted borders and forced hundreds of thousands of people from their homes.

After the Whites’ victory in Finland’s civil war, many socialist-minded Finns moved to Karelia hoping to build a workers’ paradise. After the rise of Soviet leader Josef Stalin, however, they were labeled as dangerous foreign influences. Thousands were arrested and deported, as Stalin sought to replace the population with Russian-speaking loyalists.

After decades of Russification, assimilation and migration, Karelian-speakers today represent only a small minority of the Republic of Karelia. Another small population resides in Finland, where they were resettled after the wars.

During World War II, Finland fought the Soviet Union several more times, striving to maintain its independence and even incorporate parts of Karelia. Finland managed to remain outside of the Soviet Union, but lost portions of its territory close to the Karelian border.

The Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, signed in 1948, encouraged cultural exchanges between Finland and the Soviet Union. The first joint Finnish-Soviet feature film, 1959’s “Sampo,” was a recounting of the Kalevala spearheaded by Aleksandr Ptushko, the “Disney of Soviet film” – but stripped of any nationalist symbolism.

Rising tension

In the years following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Finnish-Karelian border became once again a place of lively meeting and exchange. Through the work of organizations like Finland’s Juminkeko foundation, the heritage of the Kalevala has been explored and celebrated on both sides of the border. Finnish and Karelian folk revival and heavy metal bands drew on the Kalevala for inspiration and materials. Shopping centers developed in border towns, and tourists began crossing the border in ever increasing numbers.

The runic song traditions of the Kalevala have also inspired contemporary artists.

Yet Russia’s war in Ukraine has turned the Finnish-Russian border once again into a place of tension. Finland became a member of NATO in 2023, concerned by Vladimir Putin’s regime’s disregard for the rights of other sovereign nations. In December 2023, the Finnish government indefinitely closed the 835-mile (1,344-kilometer) land border, and is now building a fence along part of it. Meanwhile, Russia is expanding military infrastructure near the border, as European countries raise alarm about threats to NATO.

On Feb. 28, the anniversary of the day on which Lönnrot completed the first edition of the Kalevala, public buildings in Finland will fly the country’s flag. Schools and cultural institutions will organize events to celebrate the Kalevala and the cultural and political independence it helped achieve. On the other side of the border, perhaps Karelian speakers and some other inhabitants will celebrate as well. In a Russia where cultural and ethnic minorities’ activism can attract suspicion, though, any observance is likely to be far more muted: The situation remains regrettably tense “on these poor borders, the luckless lands of the North.”

(Thomas A. DuBois, Professor of Scandinavian Studies, Folklore, and Religious Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

![]()

Original Source: