(The Conversation) — At dawn on Sept. 15, 1825, a burst of cannon fire shook the ramshackle buildings of Buffalo, New York. Families raced down the main street to witness a grand ceremony, following a parade of soldiers, clergymen, Freemasons, musicians and Seneca tribesmen, including their venerable chief, Red Jacket. All surged toward St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, the frontier town’s only grand edifice.

Inside, a crowd of Christians, Jews and Native Americans were already packed together to witness the founding of Ararat, a tract of land on nearby Grand Island that was intended to be the first autonomous Jewish city-state in almost 1,800 years.

Ararat’s 400-pound cornerstone, engraved with a central Jewish tenet of faith from the Bible’s Book of Deuteronomy, rested inside the church. When the swell of the organ died down, former diplomat, political power broker and playwright Mordecai Manuel Noah – the man who had dreamed up Ararat – rose to his feet.

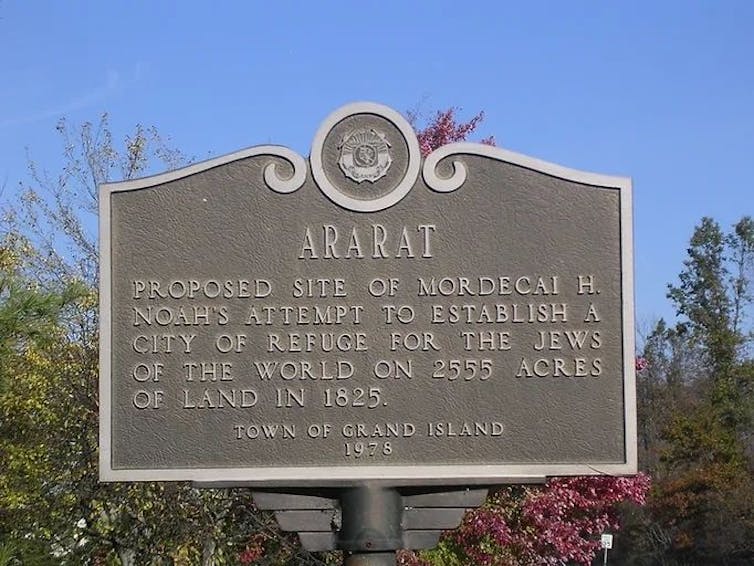

Today, this marker is one of the few surviving signs of the proposed settlement.

Adam Rovner

Described as a “stout … gentleman, with sandy hair, a large Roman nose, and … red whiskers,” Noah had draped himself for the ceremony in fur-trimmed robes borrowed from a theater. He triumphantly announced the reestablishment of “the Government of the Jewish Nation … under the auspices and protection of the constitution and laws of the United States of America.”

Noah also welcomed Native Americans, whom he – like many Americans at the time – mistakenly believed were “the descendants of the lost tribes of Israel.” In addition, he granted equal “rights and religious privileges” to the “black Jews of India and Africa,” disclosing a rare-for-his-time sensitivity toward Jews of color.

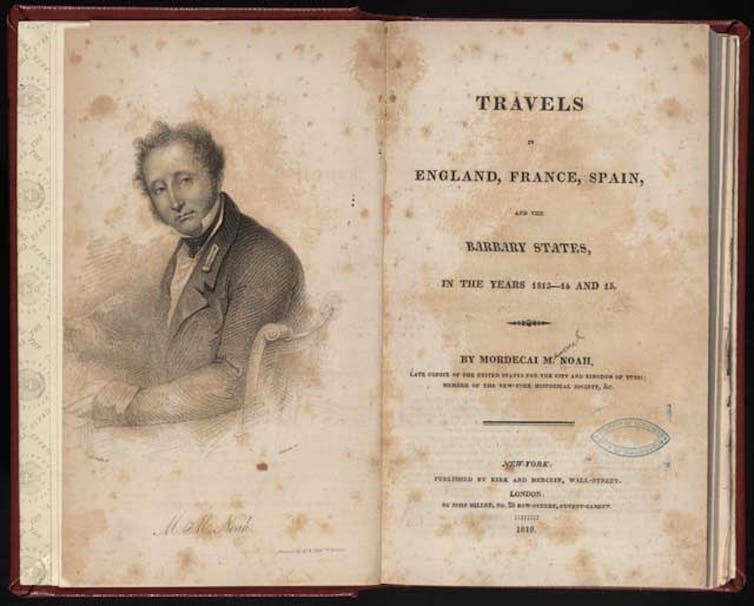

A portrait of Mordecai Noah by 19th-century painter John Wood Dodge.

Smithsonian American Art Museum via Wikimedia Commons

But Noah’s utopian ark sank with barely a trace. Not a single Jew heeded his call to settle Ararat. Noah himself abandoned ship when his calls for a Jewish republic were rebuffed by religious leaders. All that he left behind was the cornerstone.

As a scholar who scours archives to trace connections between literature and history, I’ve seen how Noah’s efforts to found a Jewish statelet have fascinated students of both American and Zionist history.

Noah was only the first of many modern thinkers to propose establishing Jewish territories far from the biblical land of Israel. In the 20th century, organizations seeking a humanitarian solution to Jewish persecution considered carving out enclaves the world over, including lands in today’s Kenya, Angola, Madagascar, Tasmania and Suriname.

‘City of refuge’

Noah wielded considerable influence in early 19th-century America through his roles as a political party boss, helming various daily newspapers, and as a popular playwright. But he was also a marginalized outsider at a time when there were fewer than 500 Jews in Manhattan, the young republic’s largest city.

Noah used his press pulpit to demand equality for Jews, even proposing himself as a presidential candidate. He remained one of few high-profile American Jews throughout his life, urging other citizens to acknowledge that one’s faith and patriotism need never be at odds. Yet antisemitic slurs dogged him throughout his career.

After witnessing the persecution of Jews in Europe during his diplomatic travels, Noah hoped Ararat would be a territorial solution to religious oppression.

‘Noah’s Ark,’ by 19th-century American painter Edward Hicks.

Philadelphia Museum of Art via Wikimedia Commons

In some ways, his efforts hearkened back to the origins of America itself. Instead of the Mayflower, Noah invoked the symbolic ark of his biblical namesake – “Ararat” is the biblical name of the mountain where the ark came to a rest after the flood. In the role of the Puritans, he cast European Jewry. And instead of Plymouth Rock, he landed on Grand Island. As the cornerstone of Ararat proclaimed, the settlement was to be a “city of refuge for the Jews” – one that Noah hoped would grow to become a state and be admitted to the American republic.

In his speeches, Noah imagined that Ararat would allow European Jews to escape persecution while simultaneously fulfilling America’s need for immigration, industry and financial capital. He also believed that his purchase of 2,555 acres of Grand Island would prove a lucrative personal investment: The recently completed Erie Canal, he reasoned, would make Buffalo a major port.

Failure to launch

At the time of Noah’s proposal, the Zionist movement – the modern political program for Jewish national self-determination – had not yet coalesced. Most Jews at the time believed that founding a Jewish state in the land of Israel was a pipe dream, or worse. God had expelled their ancestors from the Holy Land in 70 C.E., they believed, so taking matters into their own hands and rebuilding a Jewish state there would be blasphemy.

Noah hoped to sidestep those theological objections by locating a Jewish polity in the promised land of America, not the biblical promised land. Nonetheless, Jewish leaders dismissed his vision as contrary to God’s will. The chief rabbis of England and France publicly condemned Noah’s plan, and the September 1825 ceremony in Buffalo proved Ararat’s high point.

Though ridiculed in the press for Ararat’s failure, Noah took a philosophical view:

I … stand as the pioneer of the great work, leaving others to complete it. … When sneers and mockery shall have had their day … then my motives and objects will have been duly estimated and rewarded.“

The front page of one of Mordecai Noah’s books, published in 1819.

Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons

Birth of Zionism

Noah quickly resumed his career as a journalist and emerged as a kind of ambassador, penning articles and delivering speeches that linked Jewish and Christian America. To Christians, he explained Jewish practices. To his brethren, he demonstrated the fundamental compatibility between the ideals of Judaism and the United States, assuring them that America “is the country which the Almighty has blessed,” a land in which Jews “may repose in safety and happiness.”

Yet Noah never abandoned his plans for Jewish self-government and ultimately advocated national repatriation to areas of Palestine, then under Ottoman control. In 1845 he published a short book, “Discourse on the Restoration of the Jews.” A young journalist whom he had befriended, Edgar Allan Poe, praised Noah’s proposal for a Jewish return to the biblical land of Israel as “extraordinary [and] full of novel and cogent thought.”

Noah did not live to see his dreams fulfilled. After his death in March 1851, nearly 50 years passed before another playwright and journalist resurrected the idea of Jewish political autonomy: Theodor Herzl.

Herzl’s vision laid the groundwork for the establishment of the state of Israel. Today, he is considered the father of Zionism, with his image paraded on Israeli Independence Day.

Paradoxically, Noah is remembered today thanks only to the spectacular failure of his American Zion.

(Adam L. Rovner, Director of the Center for Judaic Studies, University of Denver. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

![]()

Original Source:

https://religionnews.com/2025/04/30/almost-zion-remembering-a-short-lived-jewish-state-in-new-york/