(The Conversation) — Joe Engel was and remains an icon in Charleston, South Carolina. Born in Zakroczym, Poland, he survived Auschwitz and several other concentration camps and fought with the resistance before landing on American shores as a refugee in 1949.

After retirement from his dry-cleaning business, Engel focused his later years on Holocaust education. As part of these efforts, he took to sitting on downtown park benches wearing a name tag that read “Joe Engel, Holocaust Survivor: Ask me questions” – becoming the city’s first public memorial to the victims of Nazi genocide. Knowing he would not be here to impart his message forever, Engel and his friend and fellow survivor Pincus Kolender led a drive to install the permanent memorial that now stands in Charleston’s Marion Square park.

In 2021, I moved to the city to take up my role as a professor and director of Holocaust studies at the College of Charleston. I arrived just in time to meet Engel and to teach many local students who had met him. He died the following year, at age 95.

For years, historians, educators and Jewish groups have been considering how to teach about the Holocaust after the survivors have passed on. Few of today’s college students have ever met a Holocaust survivor. Those who have likely met a child survivor, with few personal memories before 1945. American veterans of the war are almost entirely unknown to our present students; many know nothing of their own family connections to World War II.

Time marches on, distance grows, and what we call “common knowledge” changes. One alarming study from 2018 revealed that 45% of American adults could not identify a single one of the over 40,000 Nazi camps and ghettos, while 41% of younger Americans believe that Nazi Germany killed substantially less than 6 million Jews during the Holocaust.

According to a 2025 study by the Claims Conference, there are somewhat more than 200,000 survivors still alive, though their median age is 87. It is sadly expected that 7 in 10 will pass away within the next decade. With their absence near, how can educators and community members bring this history home, decreasing the perceived distance between the students of today and the lessons of the Holocaust?

Bringing history home

One method that shows promise is helping students realize the connections of their own home and their own time to a genocide that might seem far away – both on the map and in the mind.

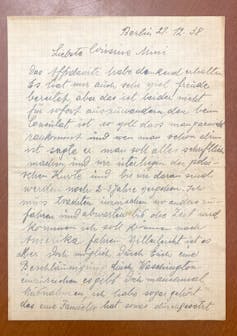

A letter dated Dec. 27, 1938, sent from Malie Landsmann to her cousin Minnie Tewel Baum of South Carolina.

Courtesy of the Jewish Heritage Collection, Addlestone Library, College of Charleston

In classes on the Holocaust, I now use a set of letters sent by a family of Polish Jews to their relatives in Camden, South Carolina. The letters themselves are powerful sources demonstrating the increasing desperation of Malie Landsmann, the main writer. In 1938, she reached out to her cousin Minnie Tewel Baum, seeking help to escape Adolf Hitler’s Germany.

Even though the two had never met, Minnie tried everything to help her cousin and her family. In the end, however, she was not successful. American immigration barriers and murderous Nazi policy took their toll, with Malie, her husband, Chaim, and their two children, Ida and Peppi, all killed at Auschwitz.

These haunting letters demonstrate the connections of the war to small-town South Carolina. They give the Holocaust a real human face and a connection to places students know.

Letter collections like these are not rare. The College of Charleston holds a second, far larger group of letters, the Helen Stern Lipton Papers, which runs to over 170 pages of correspondence between family members in South Carolina, German-occupied Europe, Russia and even Central Asia. When I was a Ph.D. student, I participated in classes using the Sara Spira postcards sent from a series of ghettos in Poland to rural Wisconsin. Further archives exist all over the United States. Most communities have connections to the Holocaust, whether via artifacts, people with direct ties or both.

The important thing is to teach in ways that can break down the mental barriers created by time and space. It is indeed the same reason that the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum created a traveling exhibit called “Auschwitz. Not Long Ago. Not Far Away.”

Learning from descendants

As teachers and professors attempt to bridge these divides, they often invite the descendants of Holocaust survivors to their classes to speak. Descendants can retell the stories of their parents’ or ancestors’ perseverance and survival, but what is more important is their ability to put a human face on these events and show how they remain relevant in the lives of so many.

The Stolpersteine memorial to the Landsmann family, installed in Berlin in 2025.

Pablo Castagnola, Anzenberger Agency. Courtesy of the Zucker/Goldberg Center for Holocaust Studies

I take these short visits a step further in a class where students train as oral history interviewers, then conduct recorded conversations with a descendant of survivors. These meetings encourage discussion of family Holocaust history, but only after the student asks the descendant about how they learned about what happened to their parent, grandparent or great-grandparent, and how this might have weighed on their own life years after the war.

This is truly the point here. The most impactful parts of these recordings are almost always the discussions of legacies; of how the families that students meet still live with the enormity of Holocaust trauma.

When a descendant tells students about the past, that is important. But when a descendant speaks of what that past means for them, their family and their community, that is so much more.

Students gain firsthand knowledge of intergenerational trauma; the difficulties of rebuilding; the prevalence of anxiety, worry and depression in survivor homes; and so much more. All of this shows students in no uncertain ways how the Holocaust still has bearing on the lives of people in our communities.

History after memory: A path forward

What’s most heartening about these methods and their successes is what they reveal about what today’s students value. In the age of AI, Big Tech and omnipresent social media, I believe it is still – and maybe even more than ever – the real human connection.

Chad Gibbs with student Leah Davenport, who arranged for Stolpersteine to be installed outside the Landsmann family’s home in Berlin.

Pablo Castagnola, Anzenberger Agency. Courtesy of the Zucker/Goldberg Center for Holocaust Studies

Students are drawn in by the local connections and open up to the stories of real people, brought to them in person. Often, they launch their own research to better understand the letters.

One of my students even helped turn them into classroom materials, now used well beyond our own college. Another did the painstaking work to have four new Stolpersteine, or Stumbling Stone, memorials installed in Berlin to commemorate the Landsmann family.

Never having witnessed them myself, I can only imagine the impact of Joe Engel’s conversations on those park benches in downtown Charleston.

Nothing will ever truly replace the voices of the survivors, but I believe teachers and communities can carry on his work by making history feel local and personal. As everything around us seems to show each day, little could be more important than the lessons of these people, their sources and the Holocaust.

(Chad Gibbs, Assistant Professor of Jewish Studies, College of Charleston. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

![]()

Original Source: